In their recent article, “America’s Climate Anxiety Map”, Axios claims that Americans across the country are increasingly distressed about climate change, and that this emotional distress can be neatly visualized in map form. That claim is misleading at best and politically constructed at worst. Why? Because the “climate anxiety” map itself looks eerily familiar—it mirrors the 2024 presidential voting map, with the most “anxious” areas neatly aligning with Democrat strongholds. The data doesn’t suggest a climate emergency; it suggests a partisan psychological phenomenon manufactured by relentless media messaging.

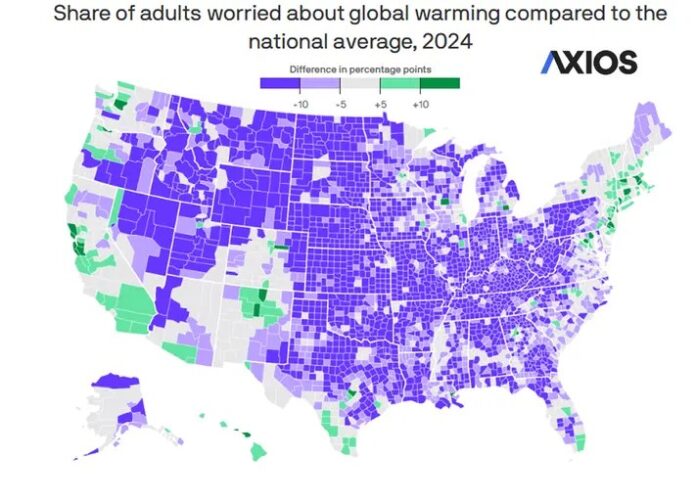

Let’s start with the map Axios published. It’s presented as a national heat map of where people feel most “anxious” about climate change, based on polling from the American Psychological Association (APA) and The Harris Poll. The darker the color, the more distress reportedly felt.

But do a simple hue shift on that image—flipping greens and blues to blues and reds—and something remarkable happens: it starts looking a lot like the 2024 electoral map by county. Red counties (which dominate the interior) show lower concern, while blue coastal urban centers light up like warning beacons of existential dread.

So, what are we really mapping here? Is it climate anxiety—or is it partisanship?

The entire premise of this map is based not on physical reality—no temperature data, no CO₂ concentrations, no storm frequencies—but on self-reported feelings.

Let that sink in. Axios and the APA are treating emotional distress as a reliable indicator of climate danger. But we know from decades of polling that political orientation has a powerful influence on how people perceive risk, especially on abstract or complex issues like climate. According to Gallup’s long-term tracking, Democrats consistently report far more concern about global warming than Republicans or independents. This has remained true even when objective metrics—like hurricane landfall trends or U.S. temperature anomalies—have shown little change.

So what this map actually reveals is not where the climate is changing the most—but where people have been most influenced by alarmist messaging.

The problem is that media narratives are driving climate perception, not actual events or trends.

If you live in New York, San Francisco, or Seattle, you’re inundated daily with headlines predicting everything from the end of snow to boiling oceans. If you believe the mainstream narrative, every heat wave is a sign of the apocalypse. Never mind that these claims often fall apart under scrutiny.

For instance, climate models used by the IPCC have repeatedly run too hot compared to observed temperatures—a fact acknowledged in the AR6 report itself. Additionally, data from NOAA and the National Hurricane Center shows no upward trend in U.S. hurricane landfalls since records began (link). In fact, some categories of extreme weather have shown declines in intensity or frequency. But those facts rarely make it into mainstream coverage.

Instead, young people are bombarded with terms like “eco-grief,” “climate trauma,” and “solastalgia”—psychological disorders supposedly caused by fear of climate change. These are not mental illnesses born from lived experience. They are constructs shaped by repetition and ideology.

The American Psychological Association, which co-sponsored this anxiety map project, has increasingly positioned itself not as a neutral observer, but as an active participant in climate activism. Their climate change resource center is filled with advocacy language, warning of the devastating psychological impacts of global warming—most of which are based on projections, not measurements.

Let’s be clear: there’s no established medical consensus that climate change is causing widespread diagnosable mental illness in the U.S. Instead, people are reporting worry, which the APA then recasts as a psychological crisis. This is classic feedback-loop thinking. The more people are told they should be terrified, the more they are—and the cycle continues.

We’ve seen this movie before. During the Cold War, some Americans lived in daily fear of nuclear annihilation. But no one suggested we map national anxiety as if it were proof that war was imminent. Anxiety is a consequence of perception, not a measure of external truth.

Strangely absent from the Axios article is any mention of actual weather trends where anxiety is supposedly highest. Did New Yorkers suffer a record number of natural disasters in 2024? Was there a heat dome over Boston? Did the Pacific Northwest burn to the ground last year?

The answer is no. In fact, U.S. wildfire acreage burned in recent years is well below the peak decades of the 1930s and 1940s, as documented by the National Interagency Fire Center. Heat waves, while attention-grabbing, are not more frequent than they were in the early 20th century. And cold extremes still regularly sweep through “climate-anxious” zones—undermining the simplistic idea that people’s emotions are a rational response to their environment.

If the fear were rooted in actual weather experience, we’d expect rural Texans and Floridians—who live with droughts and hurricanes—to top the list. But they don’t. Instead, we see anxiety clustering in university towns and media hubs.

This map also unintentionally reveals how successful climate messaging has become in certain demographics. For years, groups like Climate Central, the UN IPCC, and the U.S. Global Change Research Program have pushed increasingly dire forecasts into the public consciousness. In schools, in newsrooms, and even in mental health training, the message has been: you should be afraid. Basically, Climate messaging has become ideological grooming.

And when people—especially younger generations—report that fear, activists point to it as evidence of crisis. But it’s not. It’s evidence of indoctrination. An emotional reaction to a steady drumbeat of narrative, not a scientific appraisal of conditions on the ground.

Let’s not forget the tangible consequences of this climate-induced psychological fragility. People who believe the world is ending in 10 years are less likely to invest in their future, more likely to support extreme policy interventions, and increasingly distrustful of dissenting viewpoints. This isn’t just emotional discomfort—it’s a recipe for poor decision-making at every level of society.

And the irony? Many of the same people who are emotionally paralyzed over “climate catastrophe” live in regions with some of the lowest per capita emissions and highest standards of living in the world. They are not suffering from climate change—they are suffering from narrative fatigue.

In the end, what Axios published was not journalism. It was narrative engineering. A psychological temperature chart built not on data, but on feelings—feelings shaped by decades of one-sided storytelling and political ideology.

This is not a “climate anxiety map.” It’s a partisan vulnerability map. And The Hill, the APA, and Axios ought to be ashamed of pushing this kind of pseudo-scientific, politically driven drivel onto the public. It is simply bad journalism hiding behind a map.

The job of the press is to inform, not manipulate. But when it comes to climate, lately that line has been blurred beyond recognition.

Related

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.