EGU2025 – How the week in Vienna unfolded

Posted on 2 May 2025 by BaerbelW

Note: This blog post will be updated during EGU25 happening in Vienna from April 28 to May 2. Should recordings of the Great Debates and possibly Union Symposia mentioned below, be released sometime after the conference ends, I’ll include links to the ones I participated in.

This year’s General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) started on Monday April 28 both on premises in Vienna and online as a fully hybrid conference. This year, I decided to join the conference in Vienna for the whole week, picking and chosing sessions I was interested in. At the time of publication this blog post was still an evolving compilation – a kind of personal diary – of the happenings from my perspective.

As this post will get fairly large, you can jump to the different days, via these links (bolded days have been added already):

Monday – Tuesday – Wednesday – Thursday – Friday

The already published prolog blog post contains general explanations about the session formats as well as my planned itinerary for the week.

Monday, April 28

To start the week, I attended Union Symposia (US5) at 8:30am: Bridging Policy and Science for EU Disaster Preparedness

One of the greatest risks to our security is the impact of climate change. Extreme weather continues to ravage ever greater areas of Europe through floods, fires and droughts, throughout the year and across the European Union. The EU’s new strategic agenda for 2024-2029 states that it will strengthen its resilience, preparedness, crisis prevention and response capacities in an all-hazards and whole-of-society approach to protect its citizens and societies against different crises, including disasters. [read the rest of the abstract here]

To start the session, the conveners had a surprise for us attendees: they asked us to get together in small groups and wander from one flip-chart to the next which they had set up around the lecture hall. Each flip chart had a question and we had about 10 minutes at each to discuss the question posed on it. I was with a group tackling the question “What are the main barriers in your view to a successful interplay between science and public authorities?” We came up with these thoughts before we had to move to the next “station”: perception of scientific work as opinion pieces, vested interests, different interests, agendas, ideology, method differences, communication and vocabulary, and timeline differences. Other groups will have added their thoughts to this collection as we did with two other questions before the time allotted for this exercise was up, taking us back to our chairs.

Then it was the panelists turn to give short statements about the topic at hand:

Chloe Hill (EGU) presented a quick overview about “science for policy” in general, which included mentions of available newsletters and published policy briefs. She also introduced EGU’s new Climate Hazard and Risk Task Force and made a plug for the many policy-related sessions happening this week in Vienna.

Andrea Toreti (European Commission Joint Research Centre) explained the three main areas where “Bridging Policy and Science” plays a role:

- “Science follows Policy”: providing independent, evidence-based knowledge and science, supporting European Union (EU) policies to positively impact society.

- “Science informs Policy”: Promoting trust and collective intelligence activities for co-creation between science and policy

- “Science anticipates Policy”: providing foresight, thinking about worst-case scenarios which may have low probability. Keeping innovation and interdisciplinary in mind.

Julia Berckmans (European Environment Agency) briefly introduced the European Climate Risk Assessment (EUCRA), a comprehensive assessment of current and future climate risks in Europe.

Annika Fröwis (University of Vienna) reported on the creaition of a EUropean Higher Education Network for MAster‘s Programmes in Disaster Risk Management (EUMA) which will be a full credit masters course at the university and is currently under development. Its main objective is to deliver advanced education for Civil Protection (CP) & Disaster Risk Management (DRM) professionals.

These presentations were followed by a Q&A session tackling questions from the attendees in the room as well as collected online via Slido. The recorded session may eventually go online; if so I’ll then update the blog post with the video link.

After the coffee break, I joined session EOS2.1 at 10:45am: Open session on Teaching and Learning in Higher Education which provided examples from around the globe how higher education can tackle scientific topics.

Abstract: In this session we encourage contributions of general interest within the Higher Education community which are not covered by other sessions. The session is open to all areas involving the teaching of geoscience and related fields in higher education with a particular interest in current innovations and trends in geoscience education research. Examples might include describing a new resource available to the community, presenting a solution to a teaching challenge, pros and cons of a new educational technique/technology e.g. generative AI and chat bots, linking science content to societally relevant challenges/issues, developing critical thinking skills through the curriculum and effective strategies for online/remote instruction and/or hybrid/blended learning. Our intent with this session is to foster international discourse on common challenges and strategies for educators within the broader field of Earth Sciences – let’s share, discuss and develop effective practice.

Kristin Schulz introduced the Greenland Ice Sheet Ocean Science Network’s summer schools which brings 12 participants to Greenland for a couple of weeks for a multi-disciplinary curriculum which includes field trips, guest lectures from Greenlanders but also soft skill like critical thinking.

Lysette Davi talked about challenges and barriers to bi-national civic engagement happening in Tuscon Arizona with counterparts in Mexico. The focus of the citizens’ science project is on the water crisis i the borderlands, providing unique challenges from environmental, political and cultural functions.

Jon Xavier told us about multilevel local, national and regional education and training about climate change with the aim to develop modern, flexible and interdisciplinary curricula based on WMO’s competenencies for providing climate services for Ukraine. Online courses are currently under construction.

Okke Batelaan explained how groundwater management in the Mekon region in Vietnam was supported by geophysical training from Australia.

Mark Somogyvari talked about “Walking the River” as case studies of how to involve students in designing and conducting research based on actually walking and jotting down notes for 2 to 3 days while walking along rivers in the Berlin area in Germany for about 30km.

Michael Pointl talked about “Future Water: Lessons learned and ways forward for transdisciplinary, cross-cultural water education.” This is an international virtual free of charge offering explaining water management challenges with the help of a virtual workspace where participants create personalized avatars and can watch lectures.

Inka Koch took us on a “Water journey: from glaciers to rivers and lakes through storytelling” which is an online course piloted in 2024, focusing on recognizing water challenges and effective communication of facts in stories.

Rolf Hut talked about eWaterCycle and Teachbooks developed by the University Delft in the Netherlands.

Thomas Reimann broached the critical groundwater topic with “Interactive understanding of groundwater hydrology and hydrogeology” for which there are not enough experts.

Konstantinos Kourtidis explained the EGU’s Education Committee initiatives in support of Higher Education teaching.

After the lunch break came the short course SC1.5 Your guide to science diplomacy, introduced by Chloe Hill.

Lene Topp started the session with an explanation of what science diplomacy is and its dimensions: Science for Diplomacy (Using science cooperation to improve relations between countries), Science in Diplomacy (Informing foreign and security policy objectives with scientific advice), Diplomacy for Science (Facilitating international science cooperation by diplomatic action) and the recently added Diplomacy in Science (Using diplomatic skills and tools in and by science). She also mentioned the rapidly changing global context like increasing complexities, intensified threats by foreign interference, nations retreating from multilateralism, barriers to international scientific collaboration, misinformation.

Florian Schwendinger works closely with and for EU politicians and he shared his view that science has the potential to be a common language and that it’s vital for democracy. He encouraged attendees to take the chance to shadow MEPs, and go on a long-term project and journey.

Illias Grampas reiterated that policy makers need the best available science to make their decisions but that for example momentum for climate work has recently been lost due to quite some pushback.

During the course, several links to additional resources were shared:

Following the afternoon coffee break, I joined SC3.8 Maintaining your literature review: tools, tips, and discussions to help keep up with evolving research. As more people were interested in joining the session than chairs were available in the room and as the topic was only marginally relevant for me as a non-scientist, I left the room but followed the course via Zoom while sitting on the outside terrace. By the same Zoom connection I was able to plug our weekly New Research articles published on Thursdays by Doug and Marc, and as well in a brief conversation with the session’s conveners afterwards.

And with that, it was a wrap for Day #1 at EGU 2025 for me!

Tuesday, April 29

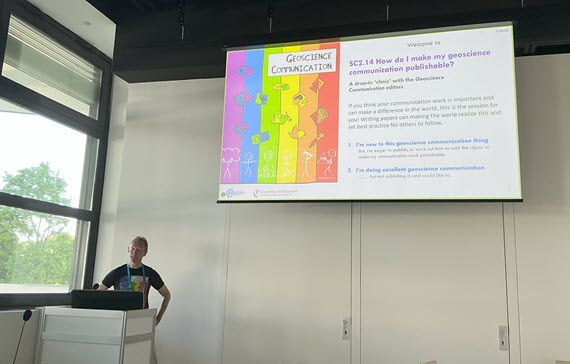

My morning started with short course SC2.14 Contributing to best-practice in geoscience communication by publishing – A drop-in ‘clinic’, with the Geoscience Communication editors as we have been working on a drafted paper for just that journal last year and I thought that it might be a good chance to gather some input about where to go with our draft. The short courses during started with John Hillier giving a short introduction about publishing with Geoscience Communication in general. They have a lot of information available on their website (here or here).

After the introduction we split up into four groups (and tables) where editors from the journal were prepared to answer one of these four questions:

- How do I get started?

- Ethics and setting up the research

- Statistics and Research Methods

- Getting a high-quality journal paper

As we already had a draft with some preliminary findings, I joined table #4 at which Kirsten von Elverfeld was prepared to answer our questions. One attendee asked about a drafted paper which – it turned out – might perhaps be better split into two. For our paper – which is about analysing data captured in a still ongoing „experiment“ on our homepage and the published rebuttals – we do seem to have ample data to proceed with the analysis even though it‘s scattered across 200 rebuttals. The findings to date may not be quite as conclusive as we‘d want them to be but we do have some options to improve this with adding about 6 months worth of data for the 2nd half of 2024 and going into more detailed discussions about what we might do differently – and ask in addition – if we re-run the experiment once we relaunched our website.

After a short break out on one of the terraces to catch a „breath of fresh air“ I made my way to hall X1 to look at some of the posters created for session ITS3.2/EOS1.9 Citizen Science and Co-creating with Communities. It‘s always interesting to at least get a glimpse of how people can become involved with science projects. In one case, ciitzens help with monitoring efforts of the air quality in Paris, in another students get involved with flying drones over specific areas and applying AI-tools to help identify debris in coastal areas on Iceland, Greenland and Svalbard.

In the afternoon I joined another short course SC1.4 Climate change, morals and how people understand the politics of climate change. It tackled the question how scientists and governments can ensure that their communication resonates more deeply with citizens without resorting to the manipulative tactics used by those who seek to undermine liberal democracy? How can scientific and government actors ensure their communications are equally meaningful and ethical? I was lucky to be in the room early, as all seats were quickly taken and late-comers had to stand or sit on the floor. So, it’s safe to say, that there was a lot of interest in the topic!

Mario Scharfbillig uses behavioural insights to improve evidence-informed policymaking and democratic processes in the EU. He is working at the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, leading the Enlightenment 2.0 research programme. He set the scene for the session with the question “The climate is changing, why aren’t we?” He explained that a large study published in 2024 showed that a large majority supports climate action but that there is also a perception gap in that many people falsely think that “others are less willing to do something than I am”.

Michael Pahle made the point that it’s easy to become – or be perceived – as a “moralizer”, a person wo supports something because s/he views it as important to her/him and a matter of right or wrong. Responsibility to act on climate change is a highly moralized issue. There is also the issue that while emissions in the EU are decreasing, the global emissions gap is widening which leads to accussations of “free-riding” which in turn can be misused by radical right parties. All in all, it’s a very fine line to navigate because the issue is so politicized or even “toxic”.

Noel Baker provided some resources, like the Union of Concerned Scientists, who offer a lot of materials. She also stressed the importance to know your audience and what their worldviews are. Depending on that information you can adjust what and how you communicate accordingly. There is for example a big difference of how to talk about climate change with people in Europe as compared to the US.

Joeri Rogelj told us about the implications of what we know about climate change for policy. He is one of the authors of the annual emissions gap report, he gives talks, writes blog posts and is active on social media in his efforts to be an “advocate for science”. One of the points he made was that useful advice contains value judgements.

Unfortunately, there were too many questions from the audience in the subsequent discussion to jot them and the answers down. Should I later find a public write-up about the session, I’ll add a link.

For the final slot of the day, I picked EOS4.2 Bridging the gap between geosciences and legal practice: informing laws and litigation which was a PICO session with a whirlwind of 12 2-minute long elevator pitches followed by up to an hour talking with the authors at their assigned large screens. April Williamsom kicked of the session with an invited presentation for which she was given 10 minutes so could go into a bit more details about Science and evidence for framework climate litigation. She mentioned some of the high-profile climate litigation cases of the last years like “Urgenda vs Netherlands” or “KlimaSeniorinnen”. Afterwards we heard about how attribution studies become more important in these cases, how speaking with lawyers can be tricky, how the Paris pledges can become a challenge if there no longer is a path available to meet the overall goal, how loss and damages from extreme weather events are still hard to pin down, how to assign responsibility for impacts and about the importance of youth-led climate litigation law suites. Quite a lot to get ones head around within about 40 minutes or so!

And with that day #2 at EGU25 ended for me.

Wednesday April 30

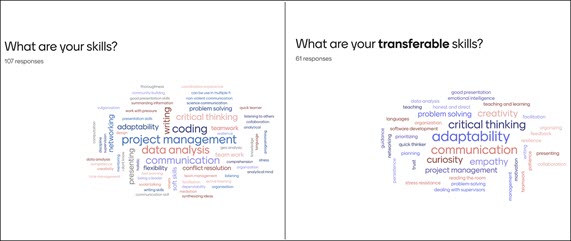

Day #3 at EGU25 started with short course SC2.5 – Transferable skills: what are they and do I have them? which was convended by Daniel Evans, Simon Clark and Veronica Peverelli. The short course started with the question of why attendees should even care about what transferable skills are and provided these bullet points as a quick answer:

- job market is competitive

- you have more competencies than you think

- Keywords + Evidence = Top of the application pile

Scientists have many transferable skills, but may not always be aware of them. To change that, Simon Clark provided a quick introduction transferable skills:

The subsequent panel discussion tackled several questions:

Q: What are seen as key skills from an employer‘s perspective?

A: Adaptability, Communication, Prepared for different field

Q: How can adaptability be shown?

A: provide personal example(s) like having moved to another country or switched from one science field to another

Q: Are there key-things academics need or already have?

A: Academics have the skills for science for policy like creating a synthesis statement, summarizing research

Q: How to communicate acadamic experience as work experience?

A: use the terms known by industry, use examples from work

At the beginning of the session, attendees were asked to add their skills to a wordcloud generated via Mentimeter. The exercise was repeated at the end of the session but specifically for transferrable skills:

Next up on my „schedule“ was GDB5 – How to translate fundamental research into societal and policy impact, convened by David Gallego-Torres, Chloe Hill, Peter van der Beek and Claudia Jesus-Rydin. This Great Debate explored the procedures to bring research results closer to policy, economy and society and touched on the differences – and similarities – between foundational and applied research. To do that, four panelists with a wide range of backgrounds had been invited to the panel:

- Nebojsa Nakicenovic, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Austria

- Lina Galvez Muñoz, European Parliament, Spain

- Agnieszka Gadzina-Kolodziejska, European Commission, Belgium

- Vasilis Stenos, Solmeyea, Greece

Some questions tackled were: How can individual researchers contribute effectively in societal and policy actions? Which mechanisms should be created to facilitate the harnessing of research results? Should the use of research results be left in the hands of dedicated professionals (e.g., officers at the research institutions)? What is the role of Scientific Advisory Boards? And where is research budget best invested?

To begin with, the panelists – two conferenced in via Zoom – gave brief statements from their different perspectives related to science for policy. As these were all done without slides, it was not easy to catch everything being said but here are a few points I noted (and I‘ll embed the recording once that becomes publicly available):

- Work to translate research into policy can be difficult due to different processes and expectations of the different institutions and organizations involved

- The public‘s trust in politicians and governments is decreasing

- Trust in scientists remains high and according to recent studies, 68% of EU citizens want to have science-based policies

- Science can improve policy-making

- Science-based policy is essential for society and democracy, esp. with the multi-crisis we are currently faced with

- There is a responsibility for researchers to get involved but it needs incentives and recognition in institution‘s assessments

- For many topics, interdisciplinary solutions are needed

- Political cycles are often short-term while we need long-term solutions

- Science might need to be somewhat simplified to get the message across

- IPCC-reports are a good example of „Science for policy“

- Funding is needed for both foundational and applied research

- „Knowledge-brokers“ who are credible for all groups involved may be needed

- Current environment with mis- and disinformation is hard to navigate for policy makers. They need to know „who to call“ if they have questions

- Science needs to take the policy cycle into account to be available when new policies are getting designed (instead of towards the end like often happens)

- Engaging to make policies better will make life better for the public

- It is not going to be easy, there will be disappointments

- Important to note: Science is not politically neutral

After the lunch-break, I went to Hall X2 to look at the posters of session EOS1.3 Games for Geosciences which provided an interesting mix of how gameplay can be utitlized in getting people interested in or understand geoscience topics. The session, convened by Christopher Skinner, Rolf Hut, Elizabeth Lewis, Lisa Gallagher and Maria Elena Orduna Alegria continued with the oral presentations in the last timeslot for the day from 16:15 to 18:00.

Out of the 10 games presented, I found two most relevant to what we do regarding science education and climate change, which is why this write-up highlights only those two. But head to the session description linked above to read the abstracts of the other presentations as well.

SCIBORG: The Science Literacy Board Game presented by Laura Coulson is a game centered around the scientific method and has the goal to strengthen scientific understanding. From the abstract:

In today’s fast-paced digital world, scientific misinformation can spread rapidly. Civic science literacy—the ability to understand how scientific knowledge is developed and evolves—is an essential skill. This skill equips individuals to better grasp how scientific understanding changes over time and critically evaluate information presented in the media, a vital component of media literacy. This is particularly crucial in areas such as climate change science. However, key aspects of science literacy are challenging to convey effectively. With traditional education systems already tasked with numerous learning objectives, complex interdisciplinary topics like scientific literacy often receive insufficient attention.

Recognizing the need for innovative approaches, our project has developed a fun and educational board game to tackle science literacy called SCIBORG. This game primarily tackles the steps of the scientific method: observation, question, hypothesis, experiment, and conclusion. The game takes place over three phases: hypothesis, experiment, and conclusion.

More information about the game is available here.

ClimarisQ: A game on the complexity of the climate systems and the extreme events was presented by Davide Faranda. The game is freely available in the app stores and can also be played in a web browser. From the abstract:

ClimarisQ is a smartphone/web game from a scientific mediation project that highlights the complexity of the climate system and the urgency of collective action to limit climate change. It is available in several languages. It is an app-game where players must make decisions to limit the frequency and impacts of extreme climate events and their impacts on human societies using real climate models. The goal of the game is to explore the effects of mitigation and adaptation choices to extreme climate events at the local, regional and global levels. Can you achieve a greener trajectory than the IPCC RCP 4.5 emission scenario by playing ClimarisQ? Explore the feedback mechanisms (notably physical, but also economic and social) that produce extreme effects on the climate system.In the game, you make decisions on a continental scale and see the impact of these decisions on the economy, politics and the environment. You will have to deal with extreme events (heat waves, cold waves, heavy rainfall and drought) generated by a real climate model. Then, you will have to try to balance the “popularity”, “ecology” and “finance” gauges as long as possible. Fulfill all the missions to explore different climates. The game-over displays both the PPM (parts per million) of CO2 deviation from the intermediate scenario of greenhouse gas emissions established by the IPCC (RCP4.5), as well as the number of survival game turns. These elements stimulate thinking about climate change and motivate the player to do better next time. Thanks to the hazards introduced by the extreme events and cards, every game is different!

More information about the game is available here.

And with this creative and “playful” session, day #3 and thereby more than half of EGU25 was complete for me.

Thursday May 1

To start my day, I joined PICO-session EOS1.6 How to communicate uncertainty to non-expert audiences, something we also have to do on Skeptical Science sometimes. Convener Sebastian Mutz set the stage with stating the somewhat obvious: „communicating uncertainty is tricky“. From the session description:

All science has uncertainty. Global challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change illustrate that an effective dialogue between science and society requires clear communication of uncertainty. Responsible science communication conveys the challenges of managing uncertainty that is inherent in data, models and predictions, facilitating the society to understand the contexts where uncertainty emerges and enabling active participation in discussions.

This was followed by an invited and therefore longer-than-usual presentation by Lottie Woods who told us about Impacting on our Lives: Using British sports and culture to explain uncertainty in climate projections.

The next speakers only had 2-minutes each for an elevator-pitch about their project or study and as it‘s rather tricky to jot down notes while also watching these rapid fire presentations, I‘ll just list them with the links to their abstracts:

Here are a few impressions from the session:

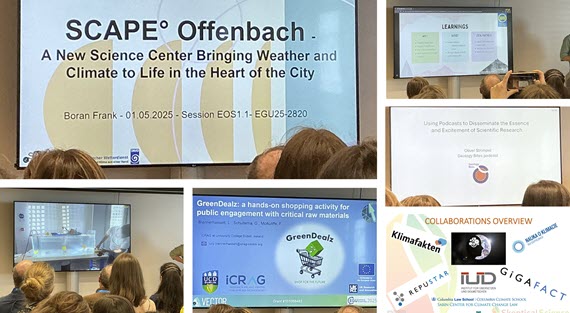

After the coffee break it was time for oral session EOS1.1 Science and Society: Science Communication Practice, Research, and Reflection in which I also had an active part with a presentation at 12:00. But first there were serveral other talks going into many different aspects of science communication:

The session started with an invited and therefore longer talk by Oliver Strimpel about Using podcasts to disseminate the essence and excitement of scientific research in which he briefly showcased several different geology-themed podcasts as well as his own, called „Geology Bites“, meant to give people a chance to dip into the topic and not like a geology course.

Thomas Gatt told us about a small-scale science communication project developed as part of a Master’s thesis and implemented in a rural Austrian community within the Hohe Tauern National Park. The initiative involved two local school classes and the general public through interactive activities and workshops. An open lecture on regional geology, given by young scientists from the University of Innsbruck, introduced the project to the wider community.

Lucy Blennerhassett explained the idea behind a currently being developed table-top game called GreenDealz about sourcing rare materials needed for example for solar modules. More information is available on the Vectorproject website.

Boran Frank presented project Scape Offenbach: New Science Center Bringing Weather and Climate to Life in the Heart of the City to get the public interested in meteorolgical and climate topics in order to increase the number of students for these topics.

Insa Thiele-Eich touched on a similar topic with University Partnership for Armospheric Sciences (UPAS): a joint effort in communicating meteorology. Among other activities, they produce videos with the same look & feel as well as podcasts with the goal to interest high-school students to study meteorology.

Milena Marjanovic answered her abstract‘s question How do we make an X-ray scan of Earth’s oceanic crust? by playing a short video of how this is done out at sea with the help of ships and seismic equipment. She then showed how this real-world activity can be simulated for classrooms with the help of a big water tank holding 300 litres of water, a ship model and some other bits and pieces.

Then it was my turn to briefly talk about our collaborations with other websites and organizations. You can read about that in this companion article already published a few days ago.

Courtney Onstad shared Preliminary Insights into Science Communication Strategies in Canadian Mining Messaging: A Mixed-Methods Perspective based on content analysis of mining-themed videos.

Eulàlia Baulenas had the last talk in the session: Storm-Resolving Earth System Models to Support Renewable Energy Transitions: mixing storyline methodologies to bridge science and society in which she suggested different types of storylines related to climate science.

During the lunch-break I’d scheduled a „pop-up networking event“ out on one of the terraces to talk about Skeptical Science and answer questions people might have about what we are doing. Based on earlier experience I wasn‘t really expecting anyobdy to show up as these events often are overlooked in the big program (and as they had been on Tuesday and Wednesday). But two young climate researchers with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts (PIK) joined me today and we talked for about 30 minutes before they had to leave for their next sessions.

I had initially planned to go to GDB3 – The Role of Large Language Models (LLMs) in Transforming Geosciences: Friend, Foe, or Fad? but with the weather being so nice outside I decided against it and spent the time starting to write today‘s summary for my diary while listening to parts of the Zoom-session for EOS1.1 started this morning.

As the last session for the day, I joined GDB7 Science and Activism – Compatible or Antithetical? which proved to be well worth the time given the quite spirited discussion among the panelists and attendees! The session was moderated by Caspar Hewett and had Sandor Mulsow (Chile), Sylvain Kuppe (France) and Ulf Büntgen (Cambridge) on the panel. After a quick introduction to the session by Caspar Hewett, each panelist had a few minutes to make an initial statement. From my jotted down notes:

- even a peer-reviewed publication can make the author be called an “activist” if the published research isn’t opportune for the government or institution

- it’s important to always be transparent of what do

- activism by scientists can make a point towards the public as in “walking the talk”

- have a debate of “HOW” to engage and not about “IF”

- scientists should not favor specific outcomes

- climate activism should clearly be kept separate from science

- overstating findings can be misleading and unhelpful

- scientists should engange and communicate with the public

- scientists should concentrate on “finding” instead of “searching” (as the latter implies searching for something specific)

After these intiial statements, attendees were invited to ask questions of the panelists and as well everybody in the room, and to add their own thoughts to the discussion. After several attendee contributions, panelists could react before the next “round” of attendee comments and questions. Due to this format, the session was very interactive and covered a lot of ground. It also meant that it was hard to jot down notes quickly and correctly enough, so I’ll just mention a few of the (pointed) questions asked and comments made:

- How do we as scientists justify not becoming activists?

- Science has the knowledge but no power – a dictator has the power but no knowledge

- What’s the role of organisations like the EGU?

I’ll embed the video as soon as it becomes available on EGU’s Youtube channel.

And with that, another eventful day at EGU25 was behind me!

Friday, May 2

Note: Day 5 of EGU25 is just getting under way when this blog post is published, so there will be more content added as it unfolds.

The first session of the day is EOS4.3 Geoethics and Global Anthropogenic Change: Geoscience for Policy, Action and Education in Addressing the Climate and Ecological Crises in which I‘ll be taling about our translation activities and challenges as the second speaker. You can alreadyread about my presentation in the companion article from where it can also be downloaded.

to be continued …

Final thoughts