Kevin Kilty

A number of people who comment and blog regularly at WUWT, the Manhattan Contrarian and other websites that allow broad opinions on climate and energy, have mixed views about the worth of Integrated Resource Plans (IRPs) that utilities are commanded to produce every two years.

Probably the majority opinion is that these are “political” documents intended to simply meet a reporting requirement of the public utility commissions (PSCs) and mollify those people in power who James Graham describes as occasionally meeting “the definition of proper fanatics”. Folks holding this “political document” opinion probably view IRPs as essentially worthless.

There is certainly evidence to support their beliefs. I spend quite a lot of my time reviewing IRPs; not only those from my own utility, but those from neighboring utilities as well, in order to write sensible public comments for our PSC. I find basic errors of fact, logic and engineering practice in them, as well as inconsistencies and errors carried forward each biennium into successive generations of IRPs.

On the other hand, I feel that PSCs offer the last line of defense against making disastrous decisions about the delivery of energy and other services. I feel that IRPs offer valuable insight into the current philosophy of a utility and the current predominant beliefs of their management, who obviously sign-off on IRPs. Errors persisting over generations of IRPs must represent honest views among people within the utility or PSC. Sometimes PSC commissioners, or people within management ranks of the utility, state these beliefs explicitly.

For example, I have written at WUWT before about the Chair of the Wyoming PSC stating at an energy conference that whereas the traditional role of a PSC is to ensure energy that is safe, reliable and affordable, “this isn’t your grandfather’s PSC any longer” and that the “PSC would never again approve a project that would release CO2 into the atmosphere.” Likewise, in a serendipitous meeting with the President of a large electric utility and a number of his management people, I was told a fantastic story about how “wind energy” could be dispatched seemingly at will, and responded by asking “How do you do such a thing?”

I am not suggesting these people are incompetent in any way. I am saying that it is easy for a person, very competent in a particular niche within an organization, to not competently understand the particulars of another niche within the enterprise nor even the business as a whole.

Moreover, I think the evolution of IRPs, how they change from one generation to the next is a valuable indicator of whether the utility is learning and moving toward a more rational view of evolving energy and service delivery or not.

Changes to how Wyoming PSC views IRPs

The Wyoming PSC has in the past viewed the IRP delivery as a pro forma process. However, the PSC recently has considered adopting a formal process for utilities to file an application for approval of their IRP and providing a formal pathway for review and adoption by the PSC. Not all PSCs allow such a formal process. The Wyoming Office of Consumer Advocate, however, provides a compelling rationale for such a process:

“Utilities should be required to submit a formal application requesting Commission approval

of their IRP. While the current process allows for public comments, a more structured application

process is necessary to ensure meaningful regulatory oversight. A formal application process enables parties to intervene, conduct discovery, access confidential information where appropriate, and present evidence or recommendations regarding whether the Commission should approve, reject, or require modifications to the IRP.”

I am firmly in favor of adopting such a formal process. Interestingly, one of the commenters to the technical conference on this topic is the Sierra Club who are also in favor of such a process. In their commentary (see Wyoming PSC Record No. 17669) they state:

“…Sierra Club makes three recommendations for the Commission’s consideration: (1) allow for contested case procedures in IRP dockets while also ensuring broad public participation through acceptance of public comment and holding of public hearings; (2) require specificity in action plans, while allowing for flexibility; and (3) clarify the actions that the Commission may take on an IRP filing.”

These are excellent reasons for supporting this effort. It shows that despite being adversaries generally in PSC hearings, as I told the Sierra Club attorney in a rate case hearing in October 2023, “We don’t always have to oppose one another.”

Of course the end goal of the Sierra Club and me are very different. They hope to use the more formal process to press for elimination of thermal generation. My goal is to avoid getting on a reckless path of system evolution. Without a formal process for IRP review, and as the Sierra Club says “(2) require specificity in action plans” the evolution of the energy system becomes dependent on piecemeal efforts through applications and hearings for a Certificate of Public Necessity and Convenience of capital projects or General Rate Cases. Such efforts can even disguise how an order approving a capital project may eventually impact a subsequent General Rate Case.

Examples drawn from IRPs

IRPs are generally very large documents provided possibly in multiple volumes – perhaps a thousand pages in total. They have sections discussing the complicated operational environment that utilities must navigate. A person will gain some sympathy for the utility by reading them.

Definitions may change from one IRP to subsequent ones. Though Wyoming has no formal review process at present, our utility has acknowledged past errors in IRPs and has made corrections. However, there is no evidence that public statements are evaluated by the utility and the corrections only appear to have come from submissions made on the utility’s official comment forms – an inconvenient route.

Something an IRP ought to be able to do is demonstrate that the utility is able to supply adequate power with the resources they claim to have or plan to have. Table 1 is from the draft of a recent (2025) IRP. It lists generating resources that a utility claims to have in 2025 and what it projects to have in years ahead without adding new resources. Then, in a later portion of the IRP the utility will add what they consider their preferred adjustments to resources.

Definitions are all important in this endeavor. In the 2025 draft IRP our utility takes numbers from the Western Resource Adequacy Program (WRAP). In contrast to earlier versions of the IRP this has added additional opaqueness and contributes to the variability of estimates.

Figure 1, Table 1

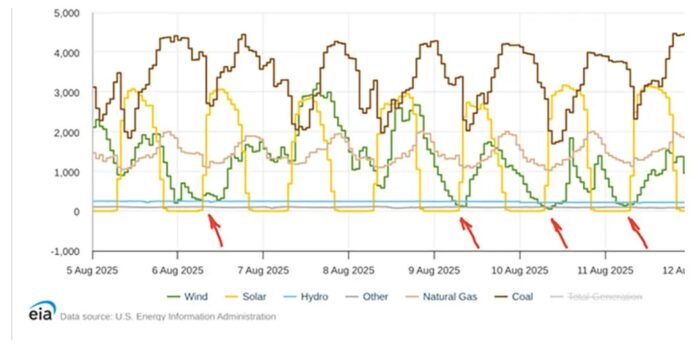

The resource categories are listed in units of MW. Once again these values are supplied by WRAP in the 2025 IRP, but they are very close to seasonal average capacity of resources that can be dispatched. Resources not capable of arbitrary dispatch, on the other hand, were in the 2023 IRP calculated by their contribution in the highest 5% intervals of demand.In other words, a sort of effective load carrying capacity (ELCC). They are now specified by WRAP but are close to earlier (ELCC) values. Despite these values being greatly depreciated, this depreciated value does not escape the inconvenient fact that wind can go to zero in any season, and solar goes to zero after hours. Figure 2 shows a week of generation by source in PACE. Note the several periods, denoted by red arrows, where wind drops to values ranging from 50MW to 200MW, well below even the heavily deprecated values (ELCC) assumed in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Obviously wind/solar present great difficulty determining resources that can be counted upon for purposes of meeting demand.

Note that one of the resource categories is “storage”. One does not store power; one stores energy. The units of this category should be megawatt hours (MWhr). However the table adds it to the other resources to determine an existing deliverable resource despite its different units. Despite violating the idea of “units”, the 2023 IRP justified the violation, thusly:

“…Certain resource types have duration limits, such that while they could be called upon in any given hour, they cannot be called upon continuously for more than specified duration. Such resources include energy storage, such as batteries or pumped hydro, as well as demand response programs and contracts, which generally have limits on consecutive hours, hours per day, and/or hours per year. As a result, while these resources are available in every hour, they are limited in how often they can be called upon for energy….These operating reserve requirements are part of the load and resource balance, and because they do not require

frequent energy dispatch, duration-limited resources are assumed to be able to provide operating reserves continuously.”

Briefly stated, the utility admits the error of what they are doing, but they do it anyway, simply because these resources are supposedly not used often. How and where does one make the transition from this thinking to handling the eventual situation when these time limited assets, along with non-dispatchable assets, come to dominate the generating mix?

Now, to the point of why adding resources of different units is simply wrong, the 939 MW of

storage which has suddenly appeared in year 2026 in Figure 1, is most likely a four-hour resource; i.e. 3,756 MW hours of energy. Since total load is listed in this table as roughly 8,000MW, the listed storage can supply only 28 minutes of system demand, but we don’t really know. In other words, adding storage as though it acts like a generation resource brings an incalculable and probabilistic element of time into the table. There is a time period over which the reserve calculation that depends on storage might be valid, but we don’t have a way to really know what it is. Adding quantities of differing units makes it seem in Table 1 like there is reasonable reserve margin, when that might be an illusion.

This carelessness of units appears in many places in IRPs, some of which are difficult to recognize. Figure 3 shows a graph of generation mix over time from a 2019 IRP with the same issue in disguise.

Figure 3

Adequacy and reserves issues

Figures 1-3 bring up a problem with resource adequacy. Perhaps the best indicator of whether or not a utility has adequate generation is its reserve margin. Using some ancillary data available from EIA suggests inadequacy in Table 1 figures. Remember that the load figure comes from WRAP. This is from data typical of July, but Figure 4 shows this to be close to an average value for the summer months. System demand or load is listed as 7,734MW and 7,485 after adjustment for actual obligations. Actual demand data from Mid-July to mid-August from EIA looks to average value 7,400MW, but there is a ±20% daily variation.

.

Figure 4.

Both the 2023 and 2025 IRPs define Planning Reserve Margin as:

“…an increase to the obligation to ensure that there will be sufficient capacity available on the system to manage uncertain events (i.e., weather, outages) and known requirements (i.e., operating reserves).”

Thus, it appears to represent a margin against contingencies as well as variation in operation. In the 2023 IRP the utility used 13%, but in the 2025 IRP WRAP has supplied the value first as 14.4% in one draft, then 16.8% in another. Who specifies odd reserve margins like 14.4% and 16.8%? These odd values are best explained as following from the North American Energy Reliability Council’s (NERC) definition of planning reserve margin which is calculated using observations

Planning Reserve Margin = (Resources – Obligations)/(Obligations) X 100%

Table 1 makes obvious use of this definition in the column for 2025 – 7,485MW X 14.4% equals 1078MW. Unfortunately this idea conflicts entirely with what the utility stated in their understanding of reserve margin.There are conflicting definitions of margin, here. Figure 4 shows that every day the peak demand for electrical energy runs well over the stated resource of 8,373MW. Thus, each day at some point there appears no reserve margin is left. Why don’t we see trouble every day, then? That is probably a function of interarea exchanges of power.[1]

What might a more useful definition of reserve margin entail?

To provide some cover for unanticipated contingencies, planning might look at resources that can be counted upon, say 95% of the time, demands that are exceeded only 5% of the time. Thus, one is looking at extremes in both generation or loads rather than averages, to cover contingencies of the outage/weather sort.

There is one more item to touch upon that relates to adequacy. The utility justified ignoring the usual rule that adding quantities with differing units together is not correct by stating that these resources are rarely used. Yet, within the IRP those same resources come to dominate the generation mix as Figure 3 shows by adding together storage plus DSM resources. As Margaret Thatcher would say “Something is logically suspect.”

The future doesn’t seem to arrive

The 2025 IRP, Table 1 in this essay, shows a declining assessment of power supply margins, year by year, through the study period. One can also see this same trend in earlier IRP versions. Yet, the trouble associated with declining margins doesn’t arrive. At the same time there is, within the preferred resource mix predicted in each IRP, a transition that doesn’t arrive. That sharp edge of energy transition in Figure 3 beginning in 2027 propagates forward as a wave too.

The utility explains this anomaly thusly:

“The rolling nature of each year’s outcome tells us that while declining reserve margins are important, the trend line is rarely followed from one year to the next. Rather, the trend line tends to be pushed forward like a wave, where the future shortage is not allowed to materialize because of cumulative actions taken within the WECC in recognition of future need.”

I have no idea whether to credit the WECC entirely, I would hope not as that speaks poorly of the utility’s planning themselves, but rather, if one looks at successive IRPs, the utility is slow-walking the closure of thermal power plants. There is an implicit admission that we can’t dispose of thermal power, yet a stubborn refusal to confront the realities of so-called renewables.

Mistakes that should have been found in proofreading

Enormous documents like these IRPs require a great deal of proofreading to catch and remove not just typographical errors, but errors that impact planning. For example Figure 5 shows highlights of goals from a 2023 IRP looked like this:

Figure 5

One could argue that a plan with total savings from energy efficiency that are two-thirds of present loads, or 1,240MW of the mysterious non-emitting peaking resources which are actually yet uninvented (although burning hydrogen is mentioned), are not realistic. Or even ask what the actual MWhr of battery storage is and how this will impact demand. Yet, the entry that jumped out at me was the 500MW now, and 1,000MW later of the advanced nuclear reactor.

Back when this 2023 IRP was ripe for release, I had just recently spoken to the CEO of TerraPower and learned that this reactor design is 1,000MWt (thermal), 350MWe (electric); so, this plan overstates the nuclear component of generation by more than one full reactor for each three built. The accumulation of errors like this can badly skew plans when the plans, themselves, rely on so many components.

In the 2025 IRP these reactors are replaced with a 300MW (electric presumably) design. I have no idea what this is.

Conclusions

IRPs are useful for illustrating the complex environment utilities are forced to grapple with. They can illuminate the culture of thinking at the utility.

I have cited a few examples to show that IRPs also commonly have typos, errors, misstatements, apparent failures of logic and conformance with data, a stubbornness of the utility to confront the reality of non-dispatchable generation, and other flaws. The enormity of these efforts almost demand improvement by having many eyes examine them. A formal process beginning with an application for approval, then having public hearings, making the utility address concerns, and issuing a final order approving the IRP would do a lot of good in this regard. It might expose the energy fabulism of the Sierra Club.[2] I hope it could convince the PSC that when it comes to what is central about public supplies of energy, it actually still is your grandfather’s PSC.

Notes and References:

1- In a PSC hearing in early March I pointed out that in the previous week there were three days out of seven when wind energy was essentially nonperforming, when obligations to export power to other balancing areas continued, and it seemed that we were importing unusually large amounts of power from the Western Area Power Administration. In turn, I showed data that the power mix at WAPA contained no wind power either, and that we were importing coal fired thermal power. There is reluctance to face such complications plaguing renewable energy.

2- Fabulism, in literature, is a genre that blends fantastical elements with everyday settings. What better describes the progressive view of energy?

Related

Discover more from Watts Up With That?

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.