I thought I wasn’t cool enough, or that I wasn’t smart enough to get it,” shrugs Zoey Deutch, reflecting on her first encounters with French New Wave cinema. That’s why the 30-year-old, sharply cast as Jean Seberg in Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, initially kept Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and their trailblazing cohort at arm’s length. “I didn’t go to film school. I’m not French, I’m not a filmmaker. All these people who are much more interesting than me like this, so I thought, ‘Maybe it’s not for me’.”

She’s not alone. Ever since Claude Chabrol kicked off the movement in 1958 with Le Beau Serge, his stark debut about alcoholism and moral decay in rural France, the Nouvelle Vague has carried a certain aloof mystique, its very existence a Gallic sneer at studio-controlled Hollywood. There are the sharp-shouldered suits and sleek rollnecks, the smoke from Gauloise cigarettes curling through Left Bank cafés, Jean-Paul Belmondo’s cocky strut. Jump cuts. Long takes. A pixie-cropped Seberg peddling the New York Herald Tribune down the Champs-Élysées. Anna Karina, Sami Frey and Claude Brasseur dancing the Madison in a shabby café when not tearing through the Louvre in Godard’s Bande à part (Band of Outsiders).

Few films today match Truffaut’s Jules et Jim for its whirlwind love triangle, Jacques Demy’s Les parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) for uncanny beauty, or Godard’s Weekend for sheer anarchic chutzpah. Elliptical in storytelling and cerebral in its provocations, the New Wave functioned as an all-out assault on convention, on bourgeois values, on cinema itself. It wasn’t so much a wave as a cutting edge: rebellious and avant-garde. A little intimidating, too – just as Deutch describes it.

Aiming to render it accessible is Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, a black-and-white divertissement about the making of Godard’s 1960 debut À bout de souffle (Breathless). “The films project a lot of rigorous intellectual stuff. And you know, if you go to the Left Bank, you do hit more politics,” the Texas director of Boyhood and the Before trilogy tells me. “But I think there was joy and exhilaration.

“They’re all very young – people coming together, making a film. To me, the Nouvelle Vague is always exciting in its looseness, its love of cinema, its freedom.” He wanted to show that films come out of communities – in this case, cinephiles clustered around Cahiers du Cinéma, the pioneering film magazine where Godard and Truffaut cut their teeth as critics. “We treat them as icons, but I wanted to go back [to their beginnings],” Linklater explains. He told his cast and crew to forget they were recreating a masterpiece; to pretend they were making a scrappy film in 1959 that probably wouldn’t amount to much. The mindset, he says, had to be: “We don’t know if this film is going to be any good; it probably won’t be. But there’s a revolution going on.”

The result is the “least pretentious film”, Deutch says of Nouvelle Vague. “If you love New Wave, you’ll love this. And if you don’t, it’s funny and warm enough to win you over.” What once discouraged her, she now knows, is not actually “an exclusive, too-cool-for-you club. When you make what’s inside of you and what you need to tell – the story that is so deep and intrinsic to who you are – that’s when people relate. That’s the New Wave.” She mentions Jules et Jim, Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 and Godard’s Pierrot le fou (Pierrot the Fool). “These movies are incredible, you know? And I hope this movie invites more people to witness and be inspired by these films that are revolutionary for a reason.”

Godard mocked the movie industry in his fractured tragedy Le mépris (Contempt) and boldly subverted the musical in Une femme est une femme (A Woman Is a Woman), but, says Linklater, Breathless will always remain his “most fun film”, an exuberant snapshot of youth and desire, infused with European cool. Truffaut had come up with the story – a Humphrey Bogart-obsessed crook shoots a cop, falls for an aspiring American journalist and lives fast until an inevitable demise – before handing it to Godard, who kept it raw. No sound department. No wardrobe. Shot on the streets of Paris. “It’s kind of like a student film,” Linklater notes. “Making a revolution.”

The movement succeeded. Its fingerprints are all over American independent cinema: Breathless, especially, influenced everyone from John Cassavetes and Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino and Noah Baumbach. It’s there in the shaggy naturalism of early 2000s “mumblecore” movies and even in the fatalism of the 1967 Hollywood classic Bonnie and Clyde.

Given how much of a phenomenon the French New Wave was, it’s easy to forget that its progenitors were all so young, a bunch of twentysomethings with borrowed cameras and scant budgets. They treated cinema, Linklater says, like jazz: loose, spontaneous, improvised. Godard famously wrote dialogue on the morning of a shoot, sometimes feeding lines to actors during takes. Varda once explained why she had turned down Madonna’s proposal to remake Cléo de 5 à 7 together: Hollywood insisted on a finished script before shooting, and Varda simply didn’t work that way. In one scene in Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague, Godard sums up the movement’s manifesto: “We believe films shouldn’t cost much. It’s the way to creative freedom.”

It set the template for indie filmmaking, says Linklater. “It’s not so much technical; it’s kind of the spirit of their movies. They lowered the stakes of cinema a little bit. It used to be, if you make a film, it better be within a genre. Is it a musical? Is it a comedy? Is it a crime film? And then what’s the genre of Breathless?” He references Truffaut’s critical writing from 1955, in which the director argued that the future of cinema would be films about love, about personal experience. “You can make a film about anything,” Linklater recalls Truffaut writing. “A trip you took, a love affair. Whatever is personal to you, whatever you’re thinking about, is worthy of a movie.” As for Godard, he once declared: “A film must have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

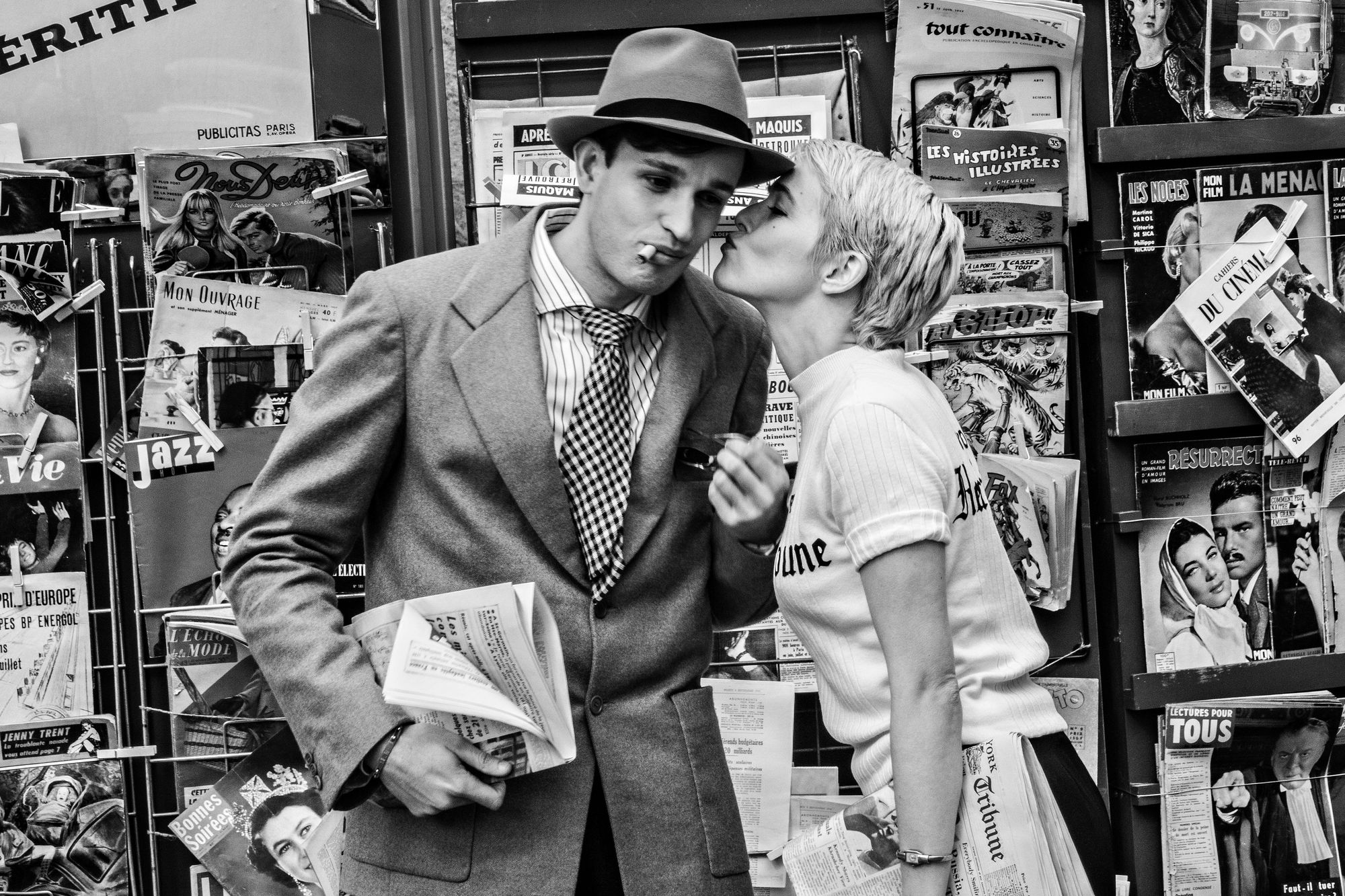

For his own movie – written in French by Holly Gent, Édouard Waintrop and Sylvain Estibal – Linklater cast unknowns, with the exception of Deutch. Guillaume Marbeck, making his film debut, plays Godard. Aubry Dullin embodies Belmondo’s smouldering insouciance, cigarette permanently dangling from his lip. And Deutch, who worked with Linklater over a decade ago on Everybody Wants Some, finally gets the role he mentioned to her when she was 19. “Rick said to me that he was working on a movie about the making of Breathless and that maybe I should play Jean Seberg, because I look like her,” she recalls. “Which I disagreed with him on, by the way.”

Marbeck’s casting story has a haphazard intensity. A photographer by trade, he’d only ever worked as an extra. His eight-hour audition began badly – with the then 29-year-old arriving late on an electric scooter to find “this mad woman” shouting at him. “I thought, the first impression is key,” he recalls. “I packed my scooter, and I go to her and I say, ‘Of course I’m late, I couldn’t find my glasses and I needed those glasses’.” She laughed. Staying in character all day, he performed scenes with prospective Belmondos, accidentally injured the casting director’s finger during a fight sequence, and somehow won Linklater over. The director gave nothing away. He simply pressed his arm and muttered, “Alright” – “I didn’t know if it was good or bad,” Marbeck recalls.

Six months of silence followed. Even when the producer finally called, she asked his opinion on which Belmondo to cast, leaving him baffled about where he stood. “At that point, I don’t understand anything about this casting,” he admits. “But I have the script. I have made it so far, so even if it’s not me, I think I deserve my place in this industry somewhere.”

Linklater’s films succeed at catching the cherished feeling that you have in your childhood and teenage years when you just experience something new and great

Guillaume Marbeck

Marbeck delivers precisely what Linklater was looking for. “Godard had this kind of confidence,” Linklater says, “that quality of a first-time filmmaker who thinks they know something.” As played by Marbeck, Godard is both puckish and infuriating behind those ever-present sunglasses, dropping gnomic epigrams between cigarette drags, and delighting in the production chaos swirling around him.

In preparation, Marbeck studied Godard’s approach and humour. “He was always the opposite,” Marbeck explains. “If a movie was really good for everyone, really well made, he would say, ‘No, it’s s***. It’s not making something new.’” He immersed himself in Godard’s film criticism – though the director’s writing, he notes, is “very foggy, like the cigarettes he smokes”, more concerned with making readers “aware of their own judgement” than with offering clear pronouncements. Marbeck channels Godard’s capriciousness – delaying shoots to achieve “a greater possibility of invention”; disregarding continuity in ways that would leave a script supervisor fuming.

For all the film’s focus on Godard, though, Nouvelle Vague isn’t a hagiography. Linklater broadens the frame to capture the camaraderie of the cinephiles that made the movement possible. Chabrol appears; so, too, do other Cahiers du Cinéma polemicists and future directors. There’s a scene at the magazine’s office where the revered Italian director Roberto Rossellini (Laurent Mothe), guest of honour at a party thrown in his name, swipes several sandwiches before joining Godard for a drive. Linklater wants you to feel how tight-knit this world was. “The early films – remember how they used to just talk about each other’s films in their films?” he says. “I didn’t have anybody when I made my first one. I had no filmmaker friends.”

The irony is that Linklater’s process is nothing like Godard’s. “I work 180 degrees different,” he explains. “Tightly scripted, well-rehearsed, everything planned.” Where Godard said that two takes were sufficient – anything more becomes “mechanical” – Linklater is all about preparation. He compares his approach to sport. “You would never tell an athlete, ‘Hey, don’t come to practice. Don’t work out, don’t train. Why don’t you come to the game and I want it to be fresh, see what happens?’ You know, you would never tell an athlete that.”

Deutch has experienced that exactitude firsthand. “I’m much more comforted by tons of rehearsal, and more takes, and more communication.” She laughs at the public perception that Linklater improvises. “I think it’s the ultimate compliment to him as a filmmaker, that people think it’s that easy.” The trick was making all that preparation invisible. “We had to recreate everything so that they could just show up and shoot,” Linklater explains. “You couldn’t be more deliberate. And yet, I was trying to still have that feeling within my film of looseness.”

Linklater took a run at the project nine years ago; no one wanted to make it. Then Godard died in 2022, and suddenly a French production company, ARP, stepped up. “I think it was Godard’s time,” Linklater reflects.

For Deutch, playing Seberg meant understanding the young actor’s fraught relationship with the shoot. The Iowa-born ingénue, then 21, had made only two films with the rigid, controlling Otto Preminger before entering Godard’s orbit. “Her experience filming Breathless was both groundbreaking and challenging,” Deutch explains. “She described it as chaotic. Godard never told her what was going to happen from one day to the next.” Seberg later said of Godard: “He wanted to capture something in me that I didn’t fully understand at the time. He wasn’t interested in who I was, just in what I could represent.”

Yet Seberg’s feelings were complex. She acknowledged Godard’s genius even while finding him “emotionally distant and sometimes manipulative”, Deutch notes. She is brilliant as Seberg. Blending kittenish charm with growing uncertainty, she captures a young woman trying to navigate Godard’s mercurial methods while still clearly bruised from Preminger’s iron-fisted direction on Bonjour Tristesse.

This is Linklater in his element, shaping a pivotal moment in cinema history into his stock-in-trade: the breezy hangout. Dazed and Confused, Linklater’s hymn to his high-school years, revolved around a group of kids giddy on youth. An equally meticulous time capsule, Nouvelle Vague bottles the same kind of energy for the budding filmmakers of late-1950s Paris, transporting us there through a propulsive jazz score and David Chambille’s exquisite celluloid cinematography. Right down to the retro reel-change marks, the film nods to Breathless without aping Godard’s disruptive style. No jump cuts here.

The very fact that Nouvelle Vague is a homage means Godard himself would probably have eviscerated it. (When Michel Hazanavicius made Redoubtable about Godard’s 1967 shoot of La Chinoise, Godard called it “a stupid, stupid idea”.) But Linklater’s kinship here isn’t so much with Godard: it’s with Truffaut. Indeed, if Godard made movies with his brain, Truffaut made movies with his heart, and it’s the latter’s sensibility – emollient and warm – that Linklater shares.

“Linklater’s films succeed at catching the cherished feeling that you have in your childhood and teenage years when you just experience something new and great,” says Marbeck. Watch Slacker, Linklater’s lo-fi 1990 debut following Austin eccentrics and drifters, and there are traces of the same DNA. “The spirit of New Wave was you didn’t need a big budget. You didn’t need the Hollywood structure,” Deutch adds. “That’s what Slacker was, right? It definitely feels New Wave to me.”

Breathless, Linklater tells me, sits exactly 65 years from cinema’s birth and 65 years from us sitting here in late 2025. “It tells you how young cinema was when Breathless came out,” he muses. “An art form that’s only 65 years old that needed reinventing, for sure.” For him, the Nouvelle Vague remains inexhaustible. “There’s still a lot to be discovered there – films that are lesser known, that are great,” he insists. “The more successful stuff got the attention, but there’s some great energy and films through that era.” He gathers his thoughts. “It’s forever inspiring.”

‘Nouvelle Vague’ is in UK and Ireland Cinemas from 30 January