Pallab GhoshScience Correspondent

Getty

GettyThe government has detailed for the first time how it aims to fulfil its manifesto pledge to work toward phasing out animal testing.

The new plans include replacing animal testing for some major safety tests by the end of this year and cutting the use of dogs and non-human primates in tests for human medicines by at least 35% by 2030.

The Labour Party said in its manifesto that it would “partner with scientists, industry, and civil society as we work towards the phasing out of animal testing”.

Science Minister Lord Vallance told BBC News that he could imagine a day where the use of animals in science was almost completely phased out but acknowledged that it would take time.

Animal experiments in the UK peaked at 4.14 million in 2015 driven mainly by a big increase then in genetic modification experiments – mostly on mice and fish

By 2020, the number had fallen sharply to 2.88 million as alternative methods were developed. But since then that decline has plateaued.

Lord Vallance told BBC News that he wants to re-ignite the fast downward trend by replacing animal testing with experiments on animal tissues grown from stem cells, AI, and computer simulations.

Asked by BBC News if he could envisage a world where animal tests were “near zero”, he said: “I think that is possible, it’s not possible anytime soon, the idea that we can eliminate animal use in the foreseeable future, I don’t think is there.

“Can we get very close to it? I think we can. Can we push faster than we have been? I think we can. Should we? We absolutely should.”

“This is a moment to really grasp that and drive these alternative approaches,” he said.

According to the government’s newly detailed plans, by the end of 2025, scientists will stop using animals for some major safety tests and switch to newer lab methods that use human cells instead.

As a former government chief scientific advisor and former head of research for a major pharmaceutical company, he will know that many scientists believe reaching “near zero” tests on animals will be extremely difficult, even in the longer term. That includes those who are the greatest advocates of non-animal methods.

“I very strongly believe that that is not possible for reasons of safety,” said Prof Frances Balkwill, of Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

Prof Balkwill is working on finding ways stop ovarian cancer recurring, using mice as well as non-animal approaches, of which she is a huge fan.

“These non-animal methods will never replace the complexity that we can see when we have a tumour growing in a whole organism, such as a mouse,” she said.

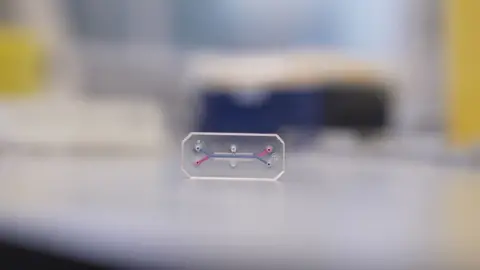

Kevin Church/BBC News

Kevin Church/BBC NewsOne of the world’s leading centres for developing alternatives to animal testing is the Centre for Predictive in vitro Models (CPM) at Queen Mary University of London.

Researchers here are developing the extraordinarily sounding “organ-on-a-chip” technology, conjuring up alarming images of throbbing brains and beating hearts sitting on top of electronic circuits.

The reality, though, is far less sci-fi.

Some small pieces of glassware containing tiny samples of human cells from different organs from the body, such as the liver or brain, are connected to electrodes which send information to a computer.

What is amazing, said the CPM’s co-director, Prof Hazel Screen, is that cells from various parts of the body can be connected together to mimic how different organs work together.

“In theory, you can build any organ on a chip. Then I can use it to test a new drug,” she said.

“And because we’re taking human cells, we should be able to do better quality science.”

The safety tests that the government says will no longer use animals by the end of this year include the practice of giving rabbits a small dose of a new drug – called the pyrogen test. It says this will be replaced by a test using human immune cells in a dish.

All tests that used animals to check for dangerous germs in medicine will also be done with cell and gene technologies, the government says.

Between 2026 and 2035, the government plans to speed up the use of non-animal techniques, including the organ-on-a-chip devices and artificial intelligence.

The proposals group animal tests into two main groups: those which could be immediately replaced because safe and effective alternatives already exist and simply need laws or guidelines to be updated; and others, where alternatives exist, but still need work to prove that they are reliable enough to be widely used.

To speed up the latter, the government plans to set up a Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods.

Ministers also promise to give an unspecified increase in funding and investment for developing new alternatives, including £30m for a research hub and more grants to support innovative methods and training.

The RSPCA has cautiously welcomed the plan, describing it as a “significant step forward”, but has urged the government to deliver.

Some scientists working with animal experiments, such as Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, are deeply concerned about what they fear may be a premature push toward alternatives, and its potential negative consequences for science and medicine.

“How about the brain and behaviour? How can you study behaviour in a petri dish? You just can’t,” he says.

“With complex areas of biology where no current non-animal model gets anything close to the real biology, how is forcibly pushing this strategy going to help?”