Feature films? What a concept. They don’t always seem to be the dominant form here at Pordenone. But this afternoon was an exception to that rule, with a triple-bill of four-to-six-reelers back to back. Welcome to a world of truly immersive narrative entertainment, It’s the future.

The day began in the shortform world, but in the presence of greatness, with the legendary, mononymic French stage actress Réjane. We saw a snippet of her comic work in Ma Cousine, where she danced the can-can, and even footage of her outside the theatre, looking very regal in a fur coat, and her funeral. But the main event was the story she made famous on stage, Madame Sans-Gêne (Henri Desfontaines, André Calmettes, 1911), in which she plays the hypergamous savvy washerwoman of the title, who eventually commands the respect of the Emperor Napoleon himself. I wished we had been able to see a little more of her comic skills (more obvious in a different print, apparently), and she can get a little lost in the flat staging of this, but still, Réjane is not to be pushed into a corner. She had presence and vigour and I bet she would done incredible, diva-ish work with a closeup. Stunning wardrobe work here too, giving us glamour and also delineating everyone by rank and status – enhanced by stencil colour. And thanks to Donald Sosin for witty accompaniment.

I’ll take the afternoon features in reverse order of favouritism, three-two-one. Mal St Clair’s sprightly if dated romcom Are Parents People? (1925) benefited from a strong comic cast, with Adolphe Menjou and Florence Vidor as the divorcing parents, and fresh-faced Betty Bronson, 18 but looking around 15, as their daughter, hoping to bring them back together, but swiftly distracted by a handsome doctor, who really shouldn’t take such an interest in his patients at the girls’ school, but, somehow St Clair makes it easier to go with the flow. George Beranger spoof John Barrymore as a diva-ish movie idol, who also shouldn’t be making eyes at Betty Bronson, but he does, so that’s that. It also benefited from some deft accompaniment from Neil Brand, making this a delightful hour of parlour larks, so long as no one takes anything too seriously.

What should be taken very seriously indeed, is venereal disease. Yes, kids, and Abel Gance is here to explain why, Le Droit à la vie (1917), in which a rake financier marries a young girl Andrée (Andrée Brabant), who does look very young indeed and despite the doctors’ orders, continues to er, live with her, after his symptoms emerge. There’s a murder, a false accusation, some shenanigans on the stock exchange, but really it was all building to feverish moneyman Pierre (Paul Vermoyal), going finally mad as the blood seeps through his head bandages and he attempts to make one last stock sale and scupper the market. Shot quickly, but effectively, this makes for a short, chilling melodrama, with Léon Mathot as the hero, being admirably noble in the midst of such foulness. This one also contained what I have to call a Taylor Swift moment. “Grandmère can’t come to the phone right now.” “Why?” “Because she’s… dead.” Andrée and Pierre should never, ever, have gotten together. Like, ever. Mauro Colombis kept this nasty tale on its toes.

Neither should Marion and Lord Angus in Maurice Tourneur’s The White Heather (1919), but no one ever listens to me. In this gorgeously photographed tartan tale Lord Angus (H.E. Herbert), like Pierre, an audacious speculator, has married Marion (Mabel Ballin), a lower-class woman, in secret. She has, as they say, borne him a child and yet he gads about burning through money in London while she is up in the Shetlands working for Angus’s relatives and having the kid raised by shepherds. You may not guess where this is going next, especially as it is adapted from a play… but for various reasons Marion feels the need to prove she really was married to Angus and that her son is legitimate, but the sad fact is that they were married on a yacht, The White Heather, “in accordance with Scottish law”, but then the boat sank – taking the paperwork with it. Can you believe it? A young John Gilbert (and savour that phrase for a while), who is sweet on Marion, takes it upon himself to help track down the yacht captain, which is in itself a diverting journey through the seedier quarters of London, but eventually there is nothing for it but to dive for the proof of the bairn’s legitimacy. The underwater sequences are very strong and were shot using the Williamson Brothers’s submarine tube. Quite a film, beautifully restored by San Francisco Film Preserve and accompanied by Stephen Horne’s touching score.

In the evening, we were treated to a double-bill of WWI comedies, perhaps as a chaser to last night’s screening: Harry Langdon’s Ruritanian rendez-vous Soldier Man (Mack Sennett, 1928), and the new MoMA restoration of Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms (1918), both preceded by more memories from David Robinson. Both hovering around the two-to-three-reel mark, but we’ll let them off as classics of 1920s slapstick. Proof that you can be funny, even while in uniform.

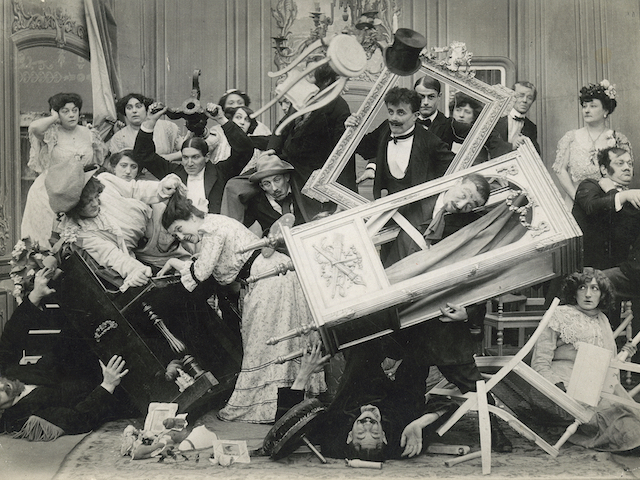

What kind of uniform? Sorry, we need to be more specific. A real highlight of the day arrived with the UCLA David C. Copley Lecture on Costume Design and Silent Cinema, this year presented by the Nasty Women Triumvirate: Maggie Hennefeld, Laura Horak, Elif Rongen-Kaynakçı. The theme was Dressed for Chaos: Costumes, Nasty Women and Social Change. But what does that mean? Well, it means a fun, informative, often rousing hour in the company of silent comediennes, and three women who dearly love them, looking at the clothes they wore on screen, and how and why. We learned how surprisingly closely the slapstick heroines’ costumes related to outfits worn by real women, easily recognised as such by the audiences, reminding us that the best comedy leans close to the truth. It meant enjoying how female comics weaponised their wardrobes, turning hats, crinolines, umbrellas and even a small lace collar, into instruments of (self)destruction. And it meant a renewed appreciation for how the cross-dressed heroines of silent comedy transgressed more than just the gender boundary. Also that these costumes were often far from fanciful, and could indeed have been lifted from the denizens of certain Paris nightclubs.

Really enjoyed this, and I am sure the presentes would want me to remind you that you too can dress up as a Nasty Woman, should you care to. Do they make pyjamas? Goodnight and I will see you tomorrow.

Intertitle of the Day

“You’re like all the women – movie mad!” Guilty as charged. That’s from Are Parents People?